Truth & Love: A Conversation with Tramaine Suubi

By Melissa Nunez, written March 2025

we are ruthless and raw

we are vengeance

with or without the lord

we turn conquest to consequence

wipe that jungle fever off your face

we are black girl juju

we are ranavalona (1778)

“long live the queen”

Cincinnati Review

Tramaine Suubi is a multilingual writer from Kampala who serves as managing editor of Writivism. She was a writer-in-residence for Yellow Arrow Publishing in 2023 and guest editor of Yellow Arrow Journal kitalo, Vol. IX, No. 2, fall 2024. Her firm beliefs in maternal community, self-reflection and self-love, and the liberation of all oppressed people make her a pivotal voice in the writing world.

Melissa Nunez, Yellow Arrow interviewer, and Tramaine met over Zoom this past January to discuss her journey as a writer, the rich impact of multilingualism on writing, and the importance of uplifting women’s stories and voices.

How did you first connect with Yellow Arrow? Can you describe your experience as a writer in residence?

I was first introduced to Yellow Arrow through a colleague of mine in my MFA program. They sent me a flyer about the writer-in-residence program because they knew I’d be in Baltimore. I thought, “Sure. Why not apply?” I was grateful to have my application accepted. Experiencing that support and community in the time of pandemic was beautiful and restorative for me. Learning more about Yellow Arrow, especially in the culmination of the residency, was a life-giving experience. In February, they hosted a reading for me at Bird in Hand and gave me access to workshops. I unfortunately did not take advantage of the workshops. But getting to know Annie [Marhefka] was a real gift. I really appreciate her and her vision, and it felt natural when they reached out to me last summer to offer my time and my space as a guest editor. They foster a continued connection and relationship with writers better than most writing organizations I’ve encountered.

What was your experience as a guest editor? What insights do you have for future guest editors and submitters?

Serving as guest editor was a humbling experience. I serve as an editor for Writivism, which is a literary organization that aspires to publish an annual anthology (including nonfiction, fiction, and poetry) supporting African diasporic writers. I came into the role with some experience, but I think it’s so different doing it for a magazine that publishes more than once a year, especially in a space where there are themes to consider. The selection process was about which pieces are the most relevant to the theme. Then it became, of these that are the most relevant, which are the strongest. That put me in a difficult place as a writer and editor, where I would see some incredible pieces and feel so heartbroken to acknowledge they did not fit the issue. The theme was about grief, kitalo, and so another interesting factor for me was making sure there was a holistic spectrum of grief in the issue. There was an imbalance of what kinds of grief were received, even though the prompt called to the whole spectrum of grief. People still lean toward grieving the deaths of loved ones. It was refreshing to receive responses to grieving pets and grieving relationships that have ended—not just romantic ones. Some of the most interesting pieces to me were people grieving past selves or grieving past lives or grieving past homes—that felt rich and resonant for me as an immigrant. I really did my best to make sure all the pieces were thematic. All the pieces were holistic in the nature of grief they chose to address or represent.

It was also important for me that we not only had racial and ethnic diversity but also diversity of age and ability. There were so many things that went into my process. I’m a highly strategic person. I live at the intersection of five different marginalized identities so I’m intentional about making sure that I curate inclusive spaces, not just for the sake of inclusion but for the sake of celebration and quality. I think we really lose quality when we’re not inclusive. I think we can lose celebration when we’re not inclusive intentionally. So that was a part of my selection process, and it really did mean that every piece that was selected fully earned its space in the issue. There were also plenty of pieces that were not selected that fully had earned a space, perhaps in a future issue of Yellow Arrow Journal.

It is so important to know as readers who may have submitted for this issue that grief is such a sensitive, loaded conversation and topic. I think every piece that was submitted has a space in a journal somewhere. I think some people were incredibly vulnerable and really challenging in their submissions, and as someone who’s received over a hundred rejection letters to different magazines, journals, and anthologies that I’ve submitted to, it was so humbling to flip the script as an editor and read such a range of submissions. Knowing there is a limit on how many essays and poems can be published, I cannot emphasize enough how much every piece that is submitted was a signal of bravery and a signal of vulnerability that is invaluable. The way pieces are rejected has so little to do with the writer themselves, and one of the best things you can do for yourself as a writer is just try, try again.

Who are some of your favorite or most inspiring women-identified writers?

I am in awe of June Jordan and her commitment to justice and love. Another writer I’m inspired by is Octavia Butler. The Parable of the Sower and The Parable of the Talents absolutely blew me away and totally reshaped how I think about organizing in community, community care, and collectivism. Yesika Salgado is inspiring to me in her love for Echo Park, for women, and for ferocity. She is the only writer of whom I’ve read all her books. She’s a Los Angeles native and she is just so committed to her El Salvadoran community and her Los Angeles community.

What first led you to writing?

I came to writing in my early 20s as a baby poet. I did not start writing creatively and regularly until I was an undergrad. Part of what led to that was my frustration with journaling. I’ve tried so hard with written and even audio journaling. It’s just so hard for me to maintain a regular practice, so I think I came to poetry from a place of humility and curiosity. I was older, I feel, than most poets are, and it was just a beautiful, safe space for me to explore and be experimental. Some of my earliest poems make me cringe, and that’s okay. I was cringe, but I was free. Poetry is my vehicle for truth. Truth is the most important thing to me in this life, and I think truth and love are synonymous. I found that I very much was the chameleon in most spaces I was in. I was a drifter, a floater, very much a social butterfly. I don’t think any of my close friends could tell you who Tramaine was. In poetry I found a space to just be whatever version of Tramaine I was in that moment and have that be enough. I did not have to hedge, or qualify, or explain it. Poetry was a space of freedom. Since then, I’ve explored fiction and I’m now slowly exploring personal essays and nonfiction.

i want to be stronger, for you, than you

will ever be. maybe i can lose

the early hours of day lying

with you, not to you. perhaps

your lifelong curls should remain

“delilah lets go”

Equatorial, Issue Six

I love alternate tales, especially those featuring women. I wholly enjoyed your poem, “delilah lets go.” What drew you to the character of Delilah?

I was raised in a strict Pentecostal household. My theological background is rich and expansive. I took 16 credits of theological courses in undergrad, and I’ve just always been deeply fascinated by the Abrahamic religions: who has a voice and who doesn’t, who tells their own story and who doesn’t, and who tells their story for them if they don’t. The Bible has 66 books and of those only two are named after women, Ruth and Esther, and they still don’t tell their own stories. I was always fascinated by who was villainized and who wasn’t in the Bible. Being raised in this strict bubble of purity culture (which, thank God, has since burst, and I’m doing a lot of healing in that area of my life), I was always stunned by how one-dimensional Delilah was. I was always confused by how singular Jezebel was. I was always fascinated by how people, women who are not wives and mothers, are treated in our storytelling and in our religions as humans. It was interesting to me that Delilah was at fault for her man planting his own downfall. There is so much tension in the story of this woman who was othered. She wasn’t Jewish; she was a Gentile. She was ‘unclean.’ There are other versions of the story where she was a sex worker! “This was intentional. She was plotting Samson’s downfall.” But as referenced in my poem, I think what solidified my draw and interest in Delilah is the song, Samson by Regina Spektor. If you’ve not listened to it, I highly recommend it.

I have always been fascinated by retellings, especially those of powerful women in history, pivotal women. We have authors like Jennifer Saint, who’s written Ariadne, and most recently, Hera. It’s just interesting to me how Delilah is this one-dimensional villainized character. That’s too easy, friends! Do we actually think that’s all there was to her? Who were her parents? Did she have siblings? What did she want in this relationship? Why did she cut the hair? Why is she so maligned for that? Where was she when Samson brought down the entire temple? Was she looking from afar? I have always taught my students (in sixth grade, ninth grade, and 12th grade English) to ask crucial questions of who is telling the story. Who is it for and who are we not hearing in the story? Delilah felt so emblematic of that to me. So yes, there is a Delilah poem, and I love that poem so much. But I want to see a Jezebel poem. I want to see a Bathsheba poem. I want to see a Tamar poem. I want to see alternative Mary poems. Who are these convenient women that we so clearly assign a role without giving thought to their hopes, their fears, their wants, their needs, their humanity?

I also read “tandem” from Sonora Review, and I love the phrase that you used, “mother each other.” Ideally, what would, or could it look like for women today to embrace that mentality?

The most important thing in life to me is friendship. I think friendship can show up in every relationship that we have with ourselves, with others, with the divine. I think one of the most profound places for restoration is motherhood and our mother-wounds that we all carry as human beings. Having learned of the phenomenon of chosen family and experienced it in real time, it’s been a gift to be mothered by the women I love that I’ve chosen to be present with me in my life. It’s been an honor for them to let me mother them. Another way to view that line is oftentimes, I think young girls and young women of color are parentified. Many of us, if you read acknowledgments, speeches, gratitudes, there’s often somewhere in there a “thank you” for an older sibling who parented you. I think that was a thought I was having when I wrote that line. And perhaps a third thought is what it means when it feels like it’s just the two of you against the world. This is a binary and is an oversimplification of perhaps a codependence, but how beautiful to care for each other in a way that a mother couldn’t or didn’t. In a healthy way, of course. We don’t want codependence; we want interdependence. What a beautiful way to mother each other and fill in the gaps where the mother may have fallen short.

laughing offbeat

but dreaming as one

so, we mother

each other

& take turns

flying off the

radar

“tandem”

Sonora Review

Could you share any writing rituals you may practice?

I actually love rituals but I’m a-ritualistic in my writing. Ever since I began writing more seriously as a creative writer at 20, I saw my writing as something to be protected. I didn’t want it to become a rigid practice in my life I was beholden to. I very intentionally never want to rely on my creative writing for my income. I think there are some writers who can do that and do that well, but I don’t think I’m one of them. I do have a few irregular practices I can think of.

I have a note on my notes app where I write down and date fragments. I also use my birthday, as opposed to December 31 or January 1, as placeholders for things to get done. I organize all my poetry in folders based on my birthdays and when it’s coming close, I sit with all those fragments and see if there is a poem I missed. I keep a word bank in my Google Drive of amazing words I’ve come across and have either never heard or never used in a poem before. A fourth writing ritual is one that is unintentional. I tend to live a lot of my life in twos. I don’t know what to do with that. I don’t know what that means or where it’s from, but I’ve noticed there’s a lot of pairs in my writing. There are poem pairs and a pattern of pairs within a poem. I’m noticing now, even as an emerging fiction and nonfiction writer, I’m still drawn to dualities and binaries. This feels contradictory because I’m all about breaking the binary: there are multitudes! But some part of my humanity or creativity is just so drawn to the opposite, to the binary and to the dual, and I think that’s probably why I strive to break it down so much in my writing.

How does multilingualism inhabit your writing? Do you feel that learning new languages, changes the way you think about and relate to words and the page?

Absolutely. I don’t know how learning a new language wouldn’t show up in a writer’s work, and I think I would question it if it didn’t. I speak four languages. I don’t have writing fluency in all four, but I do have speaking and listening fluency in all four. My languages are English, French, and my parents’ two indigenous languages, Luganda and Runyankore. My father tongue Luganda is the language that inspired the theme I chose as guest editor, kitalo. I think something beautiful and heartbreaking about language is it’s finite. We just do not have all the words for all the experiences we would like to, in one language. It’s limited. I think it took a long time for me to accept that. My multilingualism has really stepped in for me and filled gaps that I experienced in my most frequently used language of English. It’s in my poems in my collection that’s coming out this month. There’s multilingualism in a good chunk of them. It’s so funny because I learned English, Luganda, and Runyankole at the same time and so I felt like the most complete conversations I could have were with my parents and my older sister, who also speak the three languages. I could just weave in and out of it seamlessly, like “Oh, I don't have the word for this in English, but I have it in Luganda. Oh, I don’t quite have it in Luganda, but I have it in Runyankore.” Actually, my dad does not speak Runyankore well. It’s just my mother and my older sister who share that with me, and that created a beautiful intimacy. Transferring that to my writing was unavoidable. It had to be multilingual. That’s just such a big part of how I experience the world. I dream in four languages, why wouldn’t I write in four languages? It is interesting because French is a learned language for me, so I feel less comfort and less inheritance there. But I think the more I learn it, the more I feel comfortable claiming it and weaving it in here. I had a poem that actually started in French and then I just translated to English. That was a really beautiful moment of this language becoming a part of my spirit and my mind. Multilingual speakers have this whole other world they have access to. I think it’s an enhancement to any creative writing, and I think it’s really challenged me as a writer in a really good way.

Do you have any advice for women writers specifically on how to balance the mental gymnastics we often face with the necessary work in our lives?

I think it’s really humbling to receive that question, because I feel I’m so early in my journey as a woman and a writer. As someone who loves so many women and is very much a girl’s girl, I’ve had the time and space to observe that a lot of the mental gymnastics around being a woman has something to do with children. Whether it’s having them, not having them, trying to have them, trying not to have them—especially with [the current world situation] and how [people] seek to control women’s bodies more. I do not have a child and have the privilege of access to full reproductive care, but I think my advice would be to listen to yourself. Some people might misconstrue that and think they should listen and immediately follow. I didn’t say to follow everything yourself is saying. I said to listen to yourself, perhaps in lieu of quotes like, “follow your gut” or “follow your heart.” That is all nuanced and complicated. I’ve just noticed that so many women, especially nonwriters, really don’t hear themselves. If they do hear themselves, they don’t make it a daily practice to listen to themselves whether that’s mentally, emotionally, physically, or spiritually. We cannot control our thoughts always, but I think it’s really important to be tapped into them. What is my body telling me right now? What is my mind telling me right now? What is my spirit telling me right now? What are my feelings saying? You don’t have to follow what they’re saying. You don’t have to act on what they’re saying, but there’s so much to be said for self-awareness. Hopefully, once you’ve learned how to listen to yourself, I believe the second piece of advice I would give is to forgive yourself. I think so much of what I see amongst women amongst writers, and especially amongst women writers, is just a deep guilt and a deep shame. I’m sitting as someone who very much is a recovering people pleaser and a recovering perfectionist. Society imposes so much guilt and shame already we don’t need to be adding on to that ourselves. I think there’s a certain power and humility that’s been lost because women have not been taught to or encouraged to forgive ourselves. Once you learn how to listen to yourself and to forgive yourself, you become so much more open to all of who you are. I think once you’re more open to all of who you are, you’re better able to love yourself. Once you’re better able to love yourself, you’re better able to love others. I believe truth is love, and love is truth. Those are my highest ideals. Even though I love writing, I really wish that more women writers knew how to listen to themselves and actively did it. I wish they knew how to forgive themselves, and actively did it. And I think there’s a great poem that encapsulates what I mean by that second piece of advice. It’s called “Things it will take 20 years and a bad liver to work out.” It’s by Yrsa Daly-Ward: “You’d better learn to forgive yourself. Forgive yourself instantly. It’s a skill you’re going to need until you die.” I was so inspired by that. I believe you can forgive others and love others without loving yourself or forgiving yourself. But I think many women would have much richer lives and be much richer writers if we would listen to and forgive ourselves. You cannot be everything to everybody. I think I’m still learning that. Every time I find myself punishing myself or having really negative self-talk about failing to fill a role I thought I was supposed to fill, I think of Mary Oliver’s poem “Wild Geese.” That first line just anchors me: “You do not have to be good.” I wish more women knew they do not have to be good. They just have to let the soft animal of their body “love what it loves.”

& bending over backwards on cue

i do not weave tightrope anymore

my feet are reacquainted with rest

i do not miss the spiraling

“mental gymnastics”

Prompt Press

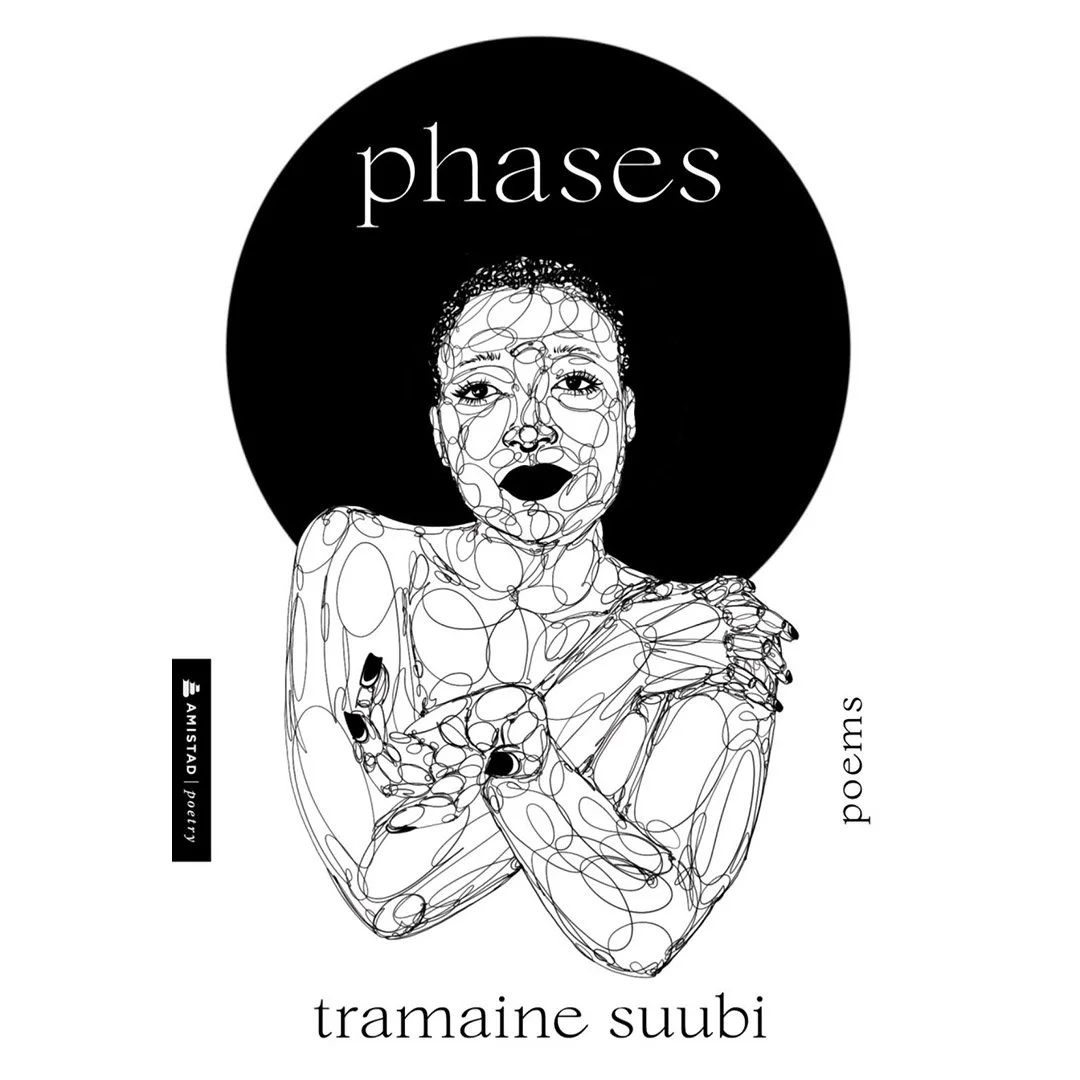

Can you share a little bit about your upcoming book Phases?

The whole process has felt surreal. phases is my debut and comes out in two weeks. It’s a full-length poetry collection of about a hundred poems. They were written anywhere from eight to four years ago. It’s so bizarre reading that book because I feel like I’m not even that person anymore. I was much younger, more stubborn, more ambitious, and surer of myself. Now I’m older and less ambitious. I’m less sure of myself and not in any self-defeating way. The older I get, the more questions I have and the less answers I’m finding. So, publishing phases has been such a process of listening to myself and forgiving myself because I’m just not that girl anymore. And that’s okay. I’m doing my best to love her and honor where she was when she wrote these poems of heartbreak and healing.

Can you share a bit more about your work with Writivism?

Writivism (which is an obvious blend of writing and activism) is a fairly young organization that was founded in 2013 in Uganda, which is where I was born, by Dr. Bwesigye Bwa Mwesigire. He’s currently an assistant professor in one of the California state universities. I think it’s Dominguez Hills, which is actually a Hispanic Serving Institution. He really had a vision of just challenging writers in Africa and the diaspora to push back against systems of oppression, colonization, and prejudice overall. To come from a place like Uganda, which is heavily censored, really living through an intense period of oppression, he unfortunately had to go on hiatus in 2019. It was really important to revamp it when we did in 2024, or 2023, just in time for the 10-year anniversary. I was brought on and was appointed as the managing editor, unpaid. It’s a small team. It’s a labor of love. We’re all in different parts of the world, all four of us. I’m really looking forward to publishing the backlog of works that were not published in between that hiatus, and I’m really excited to share with the world our 2023 anthology. We’re currently just taking a break trying to fundraise more. I don’t know how Yellow Arrow does it. I have so much respect for y’all. It’s a tougher time in the world where I think, almost just globally, the arts are being suppressed, if not blatantly attacked. Finding the resources has been difficult, but we’re optimistic. We hope to start back again with regular annual publishing in 2026. It’s been a transformative and enlightening experience.

Are there any comments or topics that I might not have touched on that are important for you to share with our readers?

I would like to emphasize that rejections of your writing are not rejections of you as a person. Your piece and the timing are being rejected for that collection. That is not a forever thing. I just really want writers to internalize that. It was really important for me as a writer and then as an editor to understand that.

Another thing I wanted to say is that individualism will not save us. We need each other. I don’t want to encourage this codependence, but I wish there was more interdependence amongst women writers. We are so much more powerful together than alone.

I also want to thank Yellow Arrow Journal for lifting up my voice and lifting up the voices of other women writers who are actively being violently oppressed in Sudan, in Kongo, in Tigray, in Falestin. I cannot tell you how powerful and how much of a lifeline writing has been for me and many of these women. I hope that one day we are all free.

You can purchase a copy of Yellow Arrow Journal kitalo, Vol. IX, No. 2, guest edited by Tramaine at the Yellow Arrow bookstore. You can secure a copy of Tramaine’s debut collection phases from Harper Collins and several online bookstores and follow her work on her website tramainesuubi.com/about.

Melissa Nunez makes her home in the Rio Grande Valley region of South Texas, where she enjoys exploring and photographing the local wild with her homeschooling family. She writes an anime column at The Daily Drunk Mag and is a prose reader for Moss Puppy Mag. She is also a staff writer for Alebrijes Review and interviewer for Yellow Arrow Publishing. You can find her work on her website melissaknunez.com/publications and follow her on Twitter @MelissaKNunez and Instagram @melissa.king.nunez.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women-identifying writers through publication and access to the literary arts. You can support us as we BLAZE a path for women-identifying creatives this year by purchasing one of our publications or a workshop from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, for yourself or as a gift, joining our newsletter, following us on Facebook or Instagram, or subscribing to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 65185, Baltimore, Maryland 21209). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.